INTRODUCTION

Mark Knoll, in his book, ‘The new shape of world Christianity: How American experience reflects global faith,’ states that Korean evangelical Christianity has been over-influenced by American Christianity. Jonathan Bonk also states that “The Korean church’s famous stress on formulas for numerical growth and the resulting corporatization of ecclesiology has given rise to serious structural and sometimes ethical problems for both churches and missions (Bonk 2015: xv).”

After concluding my research in Cambodia, I agree with Mark Knoll and Jonathan Bonk’s claim. In this paper, I argue that the number-oriented tendency of the church growth movement has a negative effect in Cambodia by South Korean missionaries.

This Paper relates to mission studies of Southeast Asia with reference to social anthropology in general but the patron-client dynamic in particular. Therefore, defining the patron-client relationship in a social anthropological context is necessary.

PATRON-CLIENT RELATIONSHIP

Although Western European feudal societies rotated around what one could term patron-client relationships, and there may be some examples in other civilizations, the patron-client relationship was first studied and published in sociology by Eisenstadt in 1956 as an article entitled ‘Ritualized Personal Relationship.’ In the analysis of the patron-client relationship, he states that “such relations are sign not just of underdevelopment, but of special types of social formations closely related to specific types of cultural orientations (Eisenstadt 1984: ix).”

From 1975 onwards, a few scholars such as Luis Roniger and R. Pain started to concur with Eisenstadt in the comparative study of patron-client relationships, publishing several papers on the subject. In his seminal book, Patrons, clients and friends: Interpersonal Relations and the Structure of Trust in Society (1984). Eisenstadt states that the themes of his research brought his study close to some of the significant works of his teacher at Hebrew University, i.e., Martin Buber, especially his work on I and Thou, and its ‘relationship-based’ understanding of interpersonal relations versus ‘social contract’ based relations. However, in subsequent social and anthropological studies, the patron-client relationship is used as the primary construction units of an interpersonal aspect of the broader social order.

According to Lindquist, the significant anthropological interest in the patron-client dynamic and brokers “does not emerge until the post-colonial era during the 1950s and 60s (Lindquist 2015: 2).” Eisenstadt also argues that from the late fifties patron-client relationship studies became more central to sociological and anthropological analysis because of the growing awareness that patron-client relationships were not destined to remain on the outskirts of society or to disappear with the development of democratic governments, economic developments, and modernization, “but new types of patron-client relationship may appear seemingly performing important functions within such more developed modern society (Eisenstadt 1984: 4).”

The articles by Eric Wolf (1956) and Clifford Geertz (1960) explicitly developed the idea of the cultural broker to describe changing forms of political authority and the transforming relationship between villages and cities following decolonization in Mexico and Indonesia. F.G. Bailey identified patron brokers as “agents of social change” (Bailey 1963: 101) that allowed for the integration of villages into a broader society in India. These papers attempted to explain the development of new forms of political and social relationships through the figure of the patron as a broker.

The terms’ patron’ and ‘client’ originated when the ordinary people of ancient Rome, plebeians (clientem), were dependent upon the ruling class, patricians (patron), for their welfare (Marshall 1998). The client was a person who had a lawyer speaking for him or her in a trial. In court, this meaning still exists today. At the same time, ‘clientela’ was a group of people who had someone speaking for them in public, the ‘patronus’ (Muno 2010: 3).

The patron-client relationship is not unique to Cambodia but is fundamentally an issue related to levels of development, and so unsurprisingly it appears also in references to South America, Africa, and Europe – especially in an agricultural society. Until recently, the use of patron-client analysis has been the domain of anthropologists who found it particularly useful in penetrating communities where interpersonal power relations were most noticeable. “Terms which are related to patron-client structures in the anthropological literature-including “clientelism,” “dyadic contract,” and “personal network” (Scott, 1972a: 92).

Since there are no formal terms in Khmer, identifying the characteristics of the patron-client relationship in other fields of study is essential. Muno suggests the following five essential characteristics of the patron-client relationship in social anthropology (Muno 2010: 4). The strategy here is to propose critical characteristics of the patron-client relationship and thereby identify the existence of the patron-client relationship between Korean missionaries and Cambodian Christians in Cambodia in general.

James Scott states that the typical patron in traditional Southeast Asia was a petty local leader. Unlike the representative of a corporate kin group or a corporate village structure, the local patron owed his local leadership to his skills, his wealth, and occasionally to his connections with regional leaders – all of which enhanced his capacity to build a personal following. In this way, patron-client systems have survived – even flourished – in both colonial and post-independent Southeast Asia (Scott 1972a: 105).

However, Scott argues that there have been substantial changes, i.e., “New resources for patronage, such as party connections, development programs, nationalized enterprises, and bureaucratic power have been created” (Scott 1972a: 105), which is the case in Cambodia.

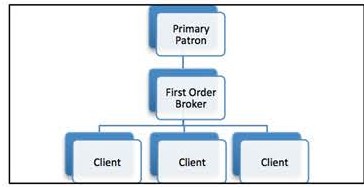

James Scott calls this ‘the patron-client pyramid’ – enlarging on the cluster but still focusing on one person and his vertical link. This is simply a vertical extension downward of the cluster in which linkages are introduced beyond the first order (Scott 1972a: 96) as shown in Diagram A below.

In reality, the First Order Broker (FOB) performs as both patron and client. FOB receives resources from the primary patron, so in that sense, they are clients. However, these resources are often managed and distributed quite independently, and practically the FOBs control these resources, so they become patrons for other clients.

In the context of Korean missionaries and Cambodian Christians, there is another patron (the Primary Patron) on top of the patron (Korean missionaries). In this way, Korean missionaries become the broker to the primary patron. Practically, there may be several levels of brokers. The sending denomination agency, e.g., Methodist Church of Korea, maybe the primary patron, but then there are the brokers, and at the end are the clients. Brokers with direct contact with clients are the first order of brokers. Korean missionaries play the role of the FOBs to Cambodian Christians, their clients.

This pyramid type of patron-client clusters is one of several ways in which Cambodians who are not close kin come to be associated. The patron-client pyramid is observed in many of the Korean missionaries’ mission structure. The primary patron is either a church or denomination from Korea, and Korean missionaries take the role of the FOB and become the connector to Cambodian Christians for finance and other resources coming from Korea.

PATRON-CLIENT RELATIONSHIP IN CAMBODIA

There are at least four types of patrons found in Cambodia for Cambodian Christians: Korean missionaries, Western missionaries, Faith Based Organizations, and NGOs. Almost all patrons, except for a few local NGOs, are organizations from outside Cambodia because status and resource difference are essential for a patron-client relationship to form in Cambodia. However, for Cambodians, the patron is always an individual or an individual representing the organization, connected through a personal relationship.

Also, from the Cambodians’ perspective, both Korean missionaries and Western missionaries have their benevolent patrons overseas. In 2008, American Protestant overseas missionaries raised a total of $5.7 billion that they distributed among 800 US agencies and 47,261 US personnel served overseas in their mission projects (Weber 2010, 166). However, many missionaries convinced themselves that their sponsors and churches back home are not like patrons of Cambodians. De Neui argues that the Western missionaries view the relationship with their supporters as task-oriented and not necessarily personal, so this kind of fund is depersonalized, and it is called ‘support’ (De Neui 2012: 110). Reese argues that Western churches are the bankers of world missions and ‘the rest of the world takes the role of negotiating for those funds through ‘partnerships.’ World mission becomes the relentless search for donors to finance the workers of other nations on the frontlines (Reese 2010: 165). In other words, from the Cambodians’ perspective, regardless of how missionaries identify their ‘support’ or ‘supporters,’ the missionaries play the role of clients to their primary patron outside Cambodia.

PATRON-CLIENT RELATIONSHIP IN KOREA

To compare and contrast the patron-client dynamic in Cambodia and Korea, we now need to understand the patron-client dynamic in Korea. There are several ways to translate the term patron-client relationship in Korea, and different translations are based on the different fields of study, but not exclusively. First, in the legal field, Nam Oyeon, in his book Public Enemy, applies the Sino-Korean term for the patron as hu-won-ja. Hu-won-ja is a combination of Chinese characters 後 (hu) 援 (won) 者(ja). Hu (後) means ‘behind,’ and won (援) has several meanings 1) help 2) pull up 3) hold or grab 4) hang on 5) save. Ja (者) means ‘a person.’ Therefore, hu-won-ja could mean ‘one who helps, pull up, hold, hang on, and save from behind.

Second, in religious studies, Park Gyeongmi, a professor in the department of Christianity of Ehwa Women’s University, also uses the term patron as hu-won-ja and client as ui-loe-in in her journal article, ‘Against Globalization by Egalitarianism of First Century Church. Moreover, in political science, Lucian W. Pye’s book, The Dynamics of Chinese Politics, into Korean, was translated as a relationship between hu-won-ja and ui-loe-in. Patron as hu-won-ja and client as ui-loe-in were the dominant choices of translation into Korean literature.

In all cases of translating of the word patron-client to hu-won-ja, hu-won-in, and hwu-kyen-in suggests a vertical or hierarchical relationship. This became evident in observing Korean missionaries’ usage of Banmal and Jeondeanmal to Cambodian pastors or when referring to them.

Banmal and Jeondeanmal

Korean missionaries’ usage of Banmal (a non-polite form of speech) and Jeondeanmal (a Polite form of speech) in reference to and speaking to Cambodians shows the hierarchical dynamics of the patron-client relationship.

There are seven speech levels in Korean, and each level has its own unique set of verb endings that indicate the level of formality of a situation. The highest six levels are grouped as jondaenmal – polite forms of speech – whereas the lowest level seven haeche is called banmal in Korean. It is informal, of neutral politeness or impolite level of speech, and used most often among close friends or when addressing younger people. It is never used between strangers, according to the chart, “unless the speaker wants to pick a fight.”

Sok Nhep states that the Khmer language is also built on a hierarchical system, as he explains in his Paper, ‘Indigenization of a National Church: A Reflection on Cambodian Church Structure’:

It (Khmer language) is built upon a hierarchical system. Thus, there are at least four levels of vocabulary. One cannot talk to God, to the king, to monks, teachers, parents, or friends, using the same vocabulary. Each set of vocabulary is used for each level of society (Sok 2001:107).

Both Korean and Cambodian societies are aware of and use different levels of language based on differences in their hierarchical structures.

Korean Honorific

Another indicator identifying a hierarchical dynamic within a patron-client relationship is the usage of honorifics. In the Korean language, honorifics are used in direct addresses, as in Chinese and Japanese. Koreans, when referring to or addressing someone superior in status, use honorific endings that indicate the subject’s superiority. Someone is superior in status if he or she is an older relative, a stranger of roughly equal or greater age, or an employer, teacher, customer, or the like. Someone is equal or inferior in status if he/she is younger, a stranger, student, employee, or the like. For example, if I am addressing a pastor, who is my friend, I will use ‘Mok Sa,’ which is ‘pastor’ in Korean. However, when I address a pastor who is older and higher in status, I will use ‘Mok Sa – Nim,’ adding the honorific ending to indicate his or her superiority.

However, in all the interview reports on Korean missionaries, I noticed that most of them rarely used the term ‘Mok Sa Nim’ when they were referring to Cambodian Christians. Similar to Foster’s observation, Korean missionaries as patrons address their clients, Cambodian Christians, with the banmal, so that the “relative status of the two partners is never in doubt (Foster 1963: 1284).”

Gap & Eul

Gap & Eul relationships of Korea can observe one aspect of the Korean hierarchical patron-client dynamics. Gap & Eul is a general term used to indicate ‘first’ and ‘second’ in the order of priority. It is also used to indicate the first of the list of ten – Gap, Eul, Byong, Jung, Moo, Ki, Kyong, Shin, Im, Kye, as in the alphabetical list order of a, b, c. Its formal usage was in the legal arena. For example, in Korean legal documents, Gap is a term describing the first party in order and Eul as the subsequent group. Then its usage spilled over to the business sector. Now, as a part of Korean business culture, Gap is a synonym for a person or a company hiring or giving the work to the other party. Also, it found its way into everyday language in Korean society.

In 2014, highlighted by the ‘Peanut Rage’ incident in New York, Gap & Eul has become one of the major social issues in Korea. According to The Washington Post on 9 December 2014, Heather Cho, the eldest daughter of Korean Air Chairman Cho Yang-ho, had been forced to resign from her position as vice president with Korean Air after an unfortunate case of managerial misconduct went viral over the weekend involving ‘macadamia nuts’:

According to Yonhap News Agency, the 40-year-old Cho was at New York’s John F. Kennedy International Airport on Friday. Sitting in first class aboard a Korean Air due to fly to Seoul, Cho was handed some macadamia nuts by a flight attendant, though she had not asked for any. Worse still, the nuts were handed to her in a bag, and not on a plate, as per Korean Air rules… Cho was upset over a serving of nuts she was given on a flight and reportedly had the plane on which she was travelling return to the gate to expel a crew member… Witnesses told the Korea Times that she shouted during the incident. The flight, with 250 people aboard, was delayed by 11 minutes as a result.

Most of the reports condemn Heather Cho and her inappropriate action as Gap, and some are even pursuing criminal charges against her, in case of any physical misconduct. The concerns people raised were not necessarily against her role as Gap but that her behavior was inappropriate for a Gap who should have been more benevolent.

The working definition of Gap & Eul, for now, is the same as the working definition of the patron-client relationship, with Gap as Patron and Eul as Client:

Gap and Eul relationships, in both formal and informal settings, is an arrangement between an individual of higher socioeconomic status or some other personal resources (Gap) who provides support to a person of lower status (Eul) who gives assistance or service in return, an arrangement which is mutually obligatory and beneficial.

Kang Joonman, the author of ‘Gap and Eul Nation,’ points out that Korea is facing difficult gap and eul problems because conglomerates as franchiser oppress the franchisee to maximize immediate profits but ultimately face the downfall of their industries. He poses the question, “Is a true partnership between gap and eul possible?” Here I am raising the same question, “Is true partnership between Korean missionaries as gap and Cambodian Christians as eul possible?” Jun Eun Hae comments in her article entitled, ‘Gap’ Controversy? We can all be Gap or Eul to someone.’ She points out in the Korean social context, how one can play the role of a gap in one situation and eul in the other, depending on the circumstances. This dual ability is true for Korean missionaries, as they play the role of eul to the primary patron and then gap to Cambodian Christians.

CHURCH GROWTH MOVEMENT

Donald A. McGavran, the Founding Dean of the School of World Mission and Church Growth at Fuller Theological Seminary in Pasadena, California, developed a model of church growth based on his own missionary experience in India, which is a church-centered mission strategy – of which evangelism and church-planting represent its highest priority. According to McGavran, the goal of the evangelization of the world can be accomplished only through the multiplication of local churches (1980: 5-8). The mantle of this movement was transferred to C. Peter Wagner of Fuller Theological Seminary, and he emphasized the crucial role of church-planting in the church growth movement by arguing that, “it is easier to give birth to a church than try to raise the dead one.” According to the Fuller Theological Seminary report, 1,500 Korean students are in their program, and 600 graduates are working in theological institutions in Korea, North America, and mission fields all over the world.

Seongho Kim States that during the 1970s and 1980s, Donald McGavran and his followers influenced Korean churches profoundly, as McGavran introduced the church growth principle as a mission strategy. Korean churches accepted the church growth scholar’s concept, i.e., that ‘churches must set their priority and make their goal for the numerical growth.’ Moreover, as a result, Korea witnessed a phenomenal growth in Korean churches, but both in Korea and in the mission field, the adverse side effects and problems were also quite evident.

The primary mission strategy for Korean missionaries in Cambodia is church-planting, but reports that its church-planting efforts are slowing down due to aid dependency – mainly financial – were addressed at a mission symposium in 2009 at Phnom Penh, Cambodia. Thyu makes the following reports on Cambodian aid dependency to the World Council of Churches in The Ecumenical Review:

The average monthly offering given by the members to their churches in Cambodia is USD $8.06. This may be compared with a Bible sold by the United Bible Society at about USD $7 and the average costs for an official church permit granted by the Ministry of Religion in Phnom Penh at around $2,000. Looking at these figures, it is evident that the church in Cambodia would not be able to function without substantial funding from outside the country or from overseas organizations working within the country. On the other hand, this dependency is also seen as one of the most significant challenges to the Cambodian church today (2012: 110).

At the Phnom Penh Symposium in 2010, Jinsup Song, a mission superintendent of Korean Methodist Churches of Cambodia, pointed out the problematical dynamics in church-planting efforts as he was sharing financial data from his denomination’s annual report. He stated that by 2011, after more than fifteen years of mission work, the financial support of 150 Cambodia church plants by Korean Methodist missionaries had reached $16,000 per month, including salaries and facility-renting fees. However, none of these 150 churches is financially self-sustaining, and he reported that the monthly budget is increasing at the rate higher than the next Methodist seminary graduates can plant.

GAP-JIL PROBLEM

The abuse of power by Gap is known as gap-jil, which means ‘doing the Gap’ in Korean. Independent UK news report this abuse of Gap by Korean politicians in Korea:

Abuse of power is known as gapjil, and on September 2016, there were 1,289 recorded cases of gapjil in South Korea with men inciting 90 percent of incidents. Men in their 40s and 50s made up more than half the cases.

Being a Gap does not automatically lead to abuse, so Gap and Gap-jil have to be addressed separately. Functioning as a Gap does not necessarily mean or lead to an abuse of power, but when a Gap abuses power, we can address the issue as Gap-jil.

Sheep Stealing and Rice Christian

For Cambodian mission work, the dependency issue has been at the forefront. Cormack argues that from the beginning, when Catholics introduced Christianity in Cambodia, those who were initially drawn to the church were needy and dependent people. The term ‘rice Christian’ refers to people who convert to Christianity out of a need for survival, rather than from a genuine desire to embrace the Christian faith. Some missionaries offered rice and other resources to people who agreed to convert to Christianity or at least appeared to convert. Cormack states that “Those who were suffering from leprosy, demon possessed, orphans, the very poor and ex-prisoners were some of the earliest members” (Cormack 2001: 61).

Regarding Korean missionaries, Timothy Park argues that they “need to avoid paternalism and missionary methods that depend on paid agents (Ma 2015: 30),” and also states the following:

Korean missionary work in the last four decades (1980-present) has been characterized as a mission from the position of strength – a mission from affluence. This fact has been both good and bad. Korea’s economic affluence has enabled the Korean churches to support missionaries, but in recent years both the church and its missionaries have tended to depend on material resources rather than on the power of the Holy Spirit. Economic affluence nurtures a dependent spirit in the minds of national workers (Ma 2015: 23).

Unfortunately, there is much evidence of this influence as it affects Korean missionaries. Such mission practice is also currently promoted as a means to grow their church plants in Cambodia.

CONCLUSION

As I have stated earlier, after concluding my research in Cambodia, I agree with Jonathan Bonk’s claim that the number-oriented tendency of the church growth movement has a negative effect in Cambodia by South Korean missionaries. Jonathan Bonk’s challenge to Korean missionaries was not “To do the right thing for the wrong reason (Bonk 2015: xvi).” In the context of the Cambodia mission, it would be church planting for the sake of planting more churches than other denominations or other missionaries. Uchimura Kanzo, when he was 65 years old, visited America in 1926 and makes the following observation:

Americans are great people; there is no doubt about that. They are great in building cities and railroads… Needless to say they are great in money… Americans are great in all these things and much else; but not in religion… Americans must count religion in order to see or show its value… To them big churches are successful churches… To win the greatest number of converts with the least expense is their constant endeavour. Statistics is their way of showing success or failure in their religion as in their commerce and politics. Numbers, numbers, oh, how they value numbers! (88-89).

If Uchimura Kanzo were alive today, he would agree with Mark Knoll’s claim that Korean evangelical Christianity has been over-influenced by American Christianity and state the following, “Koreans must count religion in order to see or show its value… To them big churches are successful churches… To win the greatest number of converts with the least expense is their constant endeavour. Statistics is their way of showing success or failure in their religion as in their commerce and politics. Numbers, numbers, oh, how Koreans value numbers!”

=================================

Robert Oh

PastorBobOh@gmail.com

Dr. Oh is the founder of Korean American Global Mission Association (2018) and Director of Life Giving Ministry (USA). He planted five Oikos Community Churches, an Asian American Church, in Southern California from 1991 to 2008. He received his Master of Divinity and Doctor of Ministry at Fuller Theological Seminary (USA) and PhD from University of Middlesex (Oxford Centre for Mission Studies), UK in 2018. He is currently teaching Philosophy at Royal University of Phnom Penh (Cambodia).